Their stories become part of Madge’s story, and somehow yours too. All of the Imperial’s well-loved usual suspects are back: Lazlo, Bernardo, Daisy, Sammy, Martha, The Beav, Hellen, Babette, and Otto Man. Pond’s story, is really about stories, their delights, and the people who tell them. Like her view from the crest of the hill, Margaret/Madge somehow sees everything both centrally and from the periphery. Pond peers at that limited but impactful gray area from an intimate distance, contemplating the impact of the decisions you make, the decisions you never wanted to make, and the decisions that are made for you. Customer also speaks to an in-betweenness: a time that marks being an impoverished adult fresh out of college but not yet an established professional a place that doesn’t mark the past or the future but the struggling present. This distance is sometimes marked in an sparse silhouetted style that disfigures character identity completely and becomes hauntingly universal. The image speaks to a kind of retrospection that the remainder of the book is filled with – a distance Pond uses to look over her past, the characters in it, and the way they shaped her. Margaret/Madge hangs onto the edge of the horizon overlooking the map – even presiding over it like the sun – perhaps trying to find her place in it, her place in the world. The map shows a sprawling landscape, Madge’s localized and extremely personal view of her home-away-from-home: The California College of Arts and Crafts, her apartment, the Imperial, and Lazlo’s house.

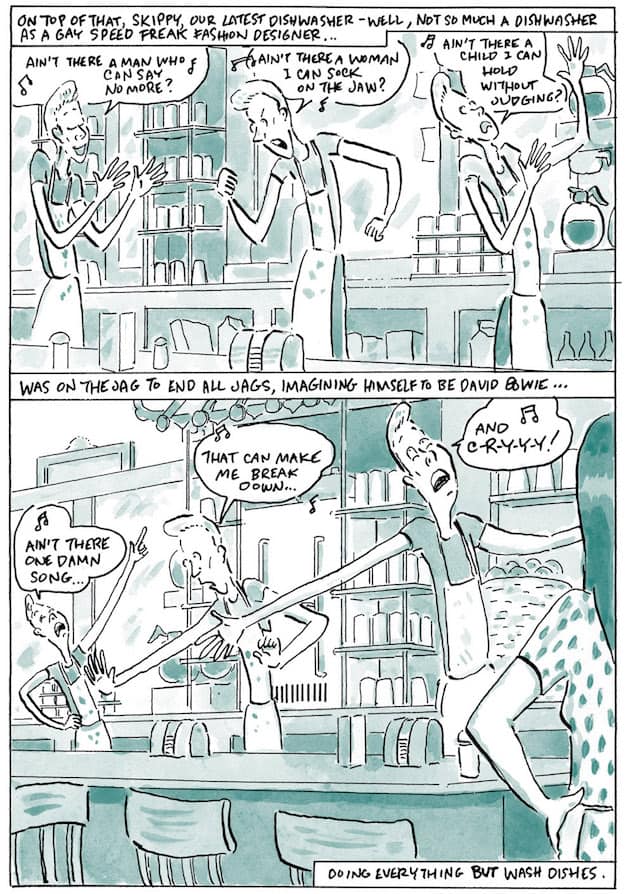

The diner’s colorful backdrop – an operatic theater set for high drama, as she refers to it – sets Margaret on track to exploring every last inch of her alter ego, Madge, and defy such conventional life choices: “I went out and slept with the first wacked out hippie I could find.†Pond’s Customer asks: What is right or wrong for our lives, and who decides? What’s the difference between what you think you want and you really need? Right or Wrong, those decisions make up our story.Įven before the second installment of episodes from the Imperial unfolds, Pond’s book opens with a beautiful double page spread of “Madge’s Oakland†on the inside fly leaf. Early in Customer, Margaret sets up the conventional expectations of adulthood – going to college, getting a house, marrying your high school sweetheart, and popping out a lot of kids – then thwarts these expectations at every turn in a quest not just to come of age but to find her identity. Her new book, The Customer is Always Wrong, picks up midstream in the Imperial’s day-to-day life where a now competent Margaret easily slides through the diner’s usual routine: sex, drugs, and coffee-slinging. Mimi Pond’s previous book, Over Easy, shows her fictionalized autobiographical self, Margaret, coming into her womanhood in the crude but charming Imperial diner.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)